Steady On.

Whatever you are using to steady your rifle, always take it with you. Shooting sticks, backpack, tripod, take it with you on every stalk, on every glassing session. No excuses.

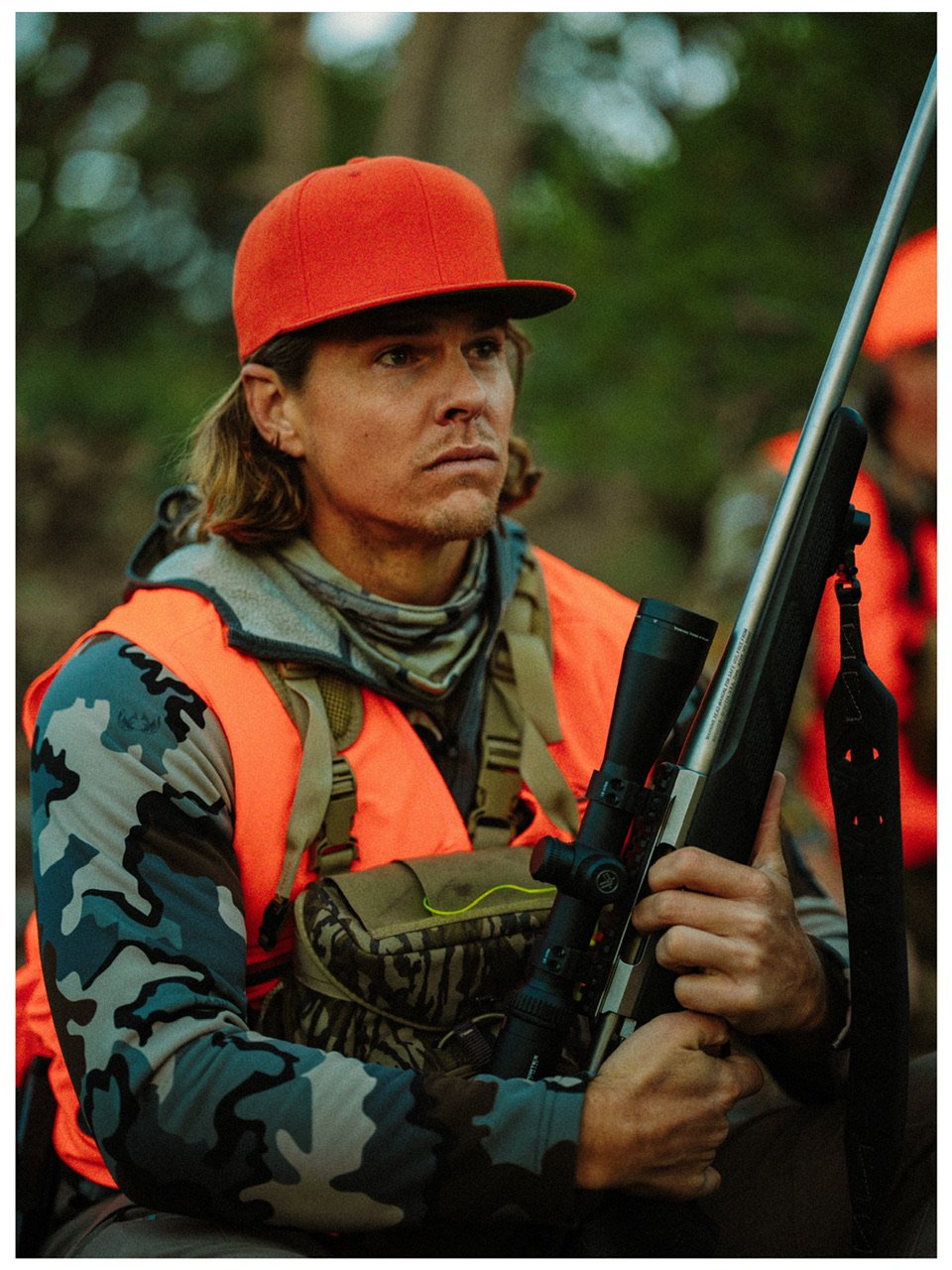

Early morning semi-darkness. Moon is out. Wool shirt, leather boots, patched pants, blaze orange hat. Diaphragm calls and bugle tube. Coffee and eggs. Eight sleepless eyes. Truck doors shut softly. Gravel roads tick, tires roll.

Red stains the sky as we come to a slow stop. Metallic clanks from natural gas extraction break the silence. Ralph pulls a small monocular out of his pack. “Can you see out of that thing?” Nash and I hassle him briefly, pulling out our binoculars and beginning to glass. “Yeah its fine” he grunts, “what are we looking for?” He puts the monocular away, shoulders his rifle and peers through the scope. “Thing won’t focus” he grumbles.

The small town of Rifle straddles the banks of the Colorado river and sits at the bottom of the valley. Eons of erosion have cut through the land, leaving bare lines of sediment in colors of tans pinks browns and parchment exposed over thousands of feet of elevation change. From near five thousand feet above sea level at the banks of the river, the precipices of the Roan Cliffs climb to over nine thousand feet to the north. To the south, the peaks of Houston and Mammoth Mountains reach up over ten thousand feet into the thin October air.

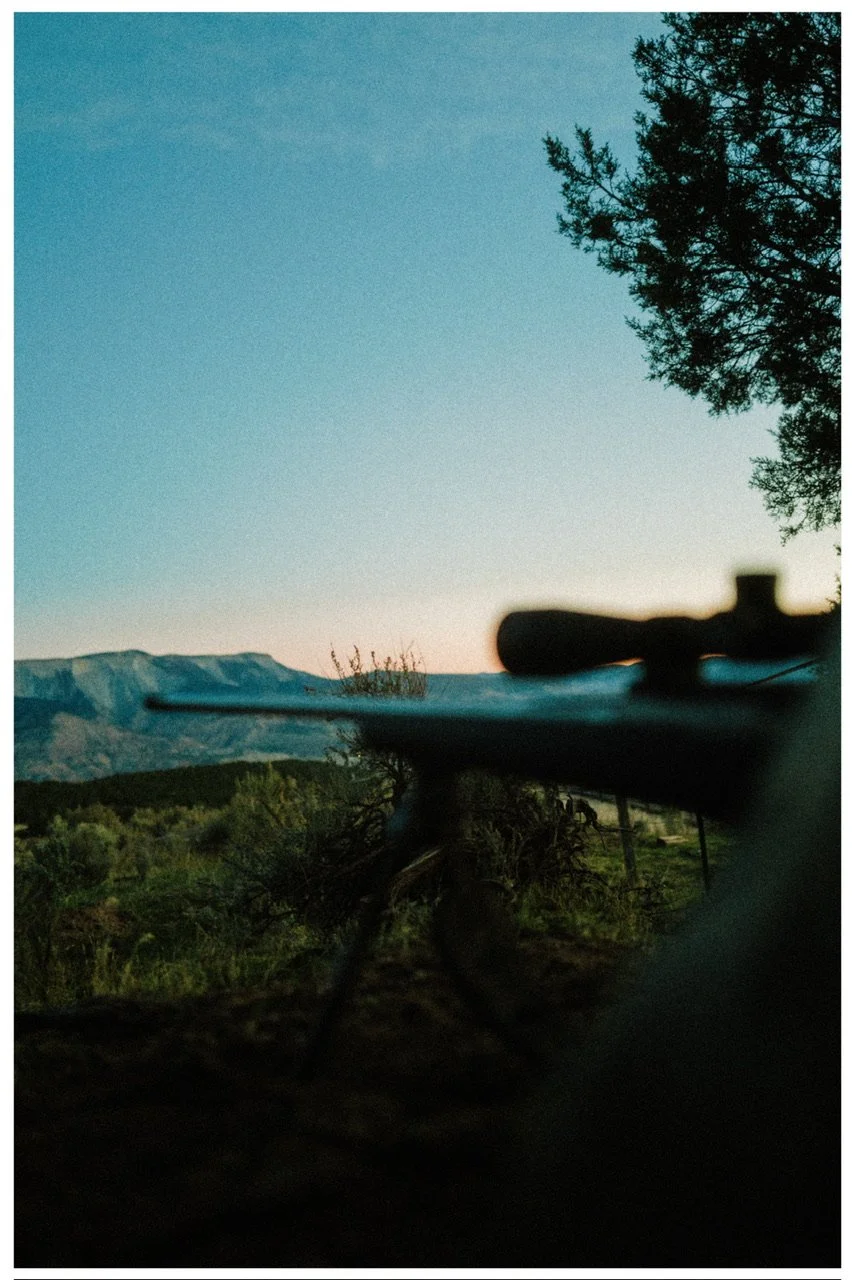

Sitting on a ridge a few miles out of town, we overlook a canyon lined with scrub brush and pine. Miles away across the valley, a mining road cuts back and forth up the opposing mountain.

Our eyes play over the sage and brush for for a glimpse of a white-patched rump or moving brown head, but we only turn up white rocks and tine-shaped branches. Elk first arrived in Colorado 4 to 5 thousand years ago and their population grew to number in the millions; however, when the state’s population started to boom thanks to their gold rush in 1848, those numbers started to nose dive. By 1910, there were less than a thousand elk left in the state.

Despite these stark numbers, conservationists in the state and back in D.C. took drastic steps to bring the elk back from the brink of extirpation. The Colorado Department of Fish and Game shut down all elk hunting from 1903 to 1933, and brought in 50 additional elk from Wyoming in 1916 to bolster the population. The Pittman-Robertson Act imposed a tax on all hunting-related equipment that was earmarked for protecting the nation’s wildlife. The Colorado Department of Fish and Game began using funds from the act to improve habitat for all species, and especially elk. Over time, the elk population rebounded thanks to these and many other private actors who lent a hand to the state, like the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation and the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership. The elk population in Colorado has grown to now number over 280,000, more than any other state in the republic.

With the most elk in the country, we should be finding something.

Despite our desire to find the elk, our green eyes don’t turn up much. Luckily, our seasoned guide Garren has a superior set of eyes for game. Scampering down the ridge to another clearing, he finds elk as Dad, Nash and I clamber after him like three ducklings following their mother.

“I’m going down further into the valley, and if they get bumped out they will cross there” Garren points to a clearing across the valley. Ranging it at 320 yards, I start to dial my scope and whisper to Ralph, “Dad get down there with Garren so you can take a short shot if you guys run into those elk.”

Thirty minutes later there are no elk to be seen, but I start to worry about Dad. He went into the shale and loose rocks of the valley without hesitation. A nine-month-old knee in his sixty-five-ish year old body gave him confidence. Over-confidence? Did I just set him up for failure?

An hour goes by before I see him motoring up the hill. Not quickly, but he’s moving. Relieved he’s ok, and anxious to get to the next glassing point, I pack up and meet everyone back at the truck.

Two mornings and evenings play out similarly as we travel from glassing knob to glassing knob, becoming familiar with the sage flats, aspen groves, natural gas drilling pads and cattle pastures that make up the thousands of acres of ranch land we have access to. We did not see many elk where we could get to them, but we were hearing them, chasing them through the underbrush, and finding sign of their presence everywhere.

The third morning we glass a pasture from below, sneaking up through a sage flat and using pine brush to hide us from where Garren expects the elk to move through. The morning is silent as fog slowly lifts. Slight movements of our jackets ruffle and spring into the air. Wincing with every movement, I try to stay still. “What’s that” I hear Nash whisper. Turning, I see the muffled sound was Dad picking up a bleach white mule deer shed. A good omen, I think, looking to the sky.

A raven glides across the blue. Garren points to it in the silence. Another good omen.

There are Elk are on the move towards us, but we have to come down off the sage brush flat, cross a salmon skin colored pasture and climb down a pine ridge if we want to head them off and keep the wind in our favor. We have to move quick.

Hustling, we make it just in time to see the herd filtering up the valley towards a dip in the hills, a saddle where two peaks come together. They may disappear out of our lives. Over thick loose rocks, under scrub pine, we scramble down one side of the valley, mirroring the herd on the opposite side. The mid-morning sun is hidden in a slight overcast. We settle as close to the herd as we dare.

Dad doesn’t have a shot, his knees and long bipod not finding purchase on the steep slope.

I take aim, crosshairs bobbing on and off a 7x7 bull with pale white horns. I struggle to find a rest, sliding down to try a tree branch then scooting back to a half kneeling position. Taking a deep breath, I try to still the movement. “280 yards” I hear Garren. The elk are moving off. I panic. A rifle shot can be like a bow shot right? If I circle the bull and slowly press the trigger, wont my subconscious put the crosshairs where they need to be?

My shot rings out. A rock under the elk explodes. No hit. A second shot does not find the mark either.

Devastation hits me as the herd spooks, running over the saddle and away onto private land we cannot access.

Hours are spent combing the area making sure the misses were clean. Nash and Dad climb around the mountain with me, other guides check in and out. No blood. Plenty of sign.

A few hours later another guide spots a limping bull. Is it the one? Did I hit him? Doubt and shame. Different bull, smaller horns in different colors. Not the white-horned bull.

The color of antlers comes from a mix of genetics and what that bull has been rubbing on or rolling in. Rather than dark horns from rubbing pine, the antlers of the bull I’d missed looked like he’d been wallowing in a chalk-filled wash.

I should have moved up the hill to a bench where I could have gone prone. My bipod was not long enough to make up for the steep slope. I should have had my tripod ready, or my pack back at the truck. A rifle shot is not a bow shot, and I shouldn’t even take a bow shot shaking on and off the entire animal. In a calmer state, I know these things and feel my inexperience as a rock at the bottom of my stomach churning.

I took the afternoon to make sure my sights were on, shooting forty rounds at 200 yards to make sure the gun and I were dialed-in.

The gun is fine.

Shooting off a bipod with my bino harness as a rear bag, the rifle’s best groups were less than an inch at 200 yards with a few fliers at two inches. Just a used Tikka I picked up at my local gun shop years ago, but it is shooting as good or better than it ever has.

Misses are mine.

Tail between my legs but not ready to quit, we keep scouring the land for another opportunity. We sat in blinds at the bottom of of a valley near the edge of where pasture fields meet rolling hills and mountains. We sat ledges overlooking the river, in sage flats and pasture land.

We climbed up the mountains to look down on fields of fresh grass across red and orange scrub. We watched a huge herd bull sit at ease on private property, nearly on someone’s front porch, and right on the mighty Colorado river where we could not hunt. That bull oozed confidence with a harem of hundreds of cows. You can’t get me.

On the evening of the fourth day, Garren took us to the bottom of a terraced pasture, the peak of which lay eight or nine hundred yards away crested with pine. A bull and a few cows stepped out of the evergreen with only thirty or so minutes of legal light left.

I looked at Dad “Go!” He whisper-shouted at me, “I’ll move around in case they spook down the hill.”

Garren and I doubled over and moved to where the terraces blocked us from the elk’s sight and started sprinting up the grassy hill, Nash falling in behind us. We made it up four hundred yards and had to drop into a small drainage to keep out of sight.

Still running, we went nearly to all fours as we hustled another two hundred yards up hill. Huffing and puffing, we rested and then popped up out of the drainage.

“200 yards” Garren ranged the bull, “It’s small, not as big as your bull last year.” Uncertainty briefly crossed my mind, “Should I shoot him?”

“Let’s do this” I said as I stood up and took aim. There was no rest to find or ridge to work up to so I could get prone. We didn’t have time. I had to stand and deliver. “Let’s go” I told myself.

As I went to fire on the small bull, a cow stepped behind him “Don’t shoot now” Garren hissed. We had only fifteen or so minutes of light. Holding my breath and keeping aim, the bull stepped away and I had a shot. I pulled on the trigger. Turned the safety off. Pulled on the trigger again. “I think you missed,” Garren pointed out as the bull’s head shot up and I quickly racked another round. I hit him with my second shot and he took off, running to the left as the cows ran straight away. I put two more rounds into him while he ran, anchoring him about 50 yards from where he first stood.

As is almost never the case, the bull was bigger on the ground than we thought, a thick antlered yet short 5x6 (anything you can hang a ring on). Gratitude, embarrassment and elation combined.

I field dressed the bull in the shadows of headlights and F250 headlamps, insisting on doing it myself when Garren would’ve done a better job quicker. With four of us and the luck of shooting the bull on relatively flat pasture, the bull went up into the truck bed easily. After pictures, smiles, and texts to my buddies, we drove over the river and back to the home we were staying in. My mother-in-law Kathy came out holding my son Ralph, both of their eyes wide.

We popped the tailgate and I hopped in, reaching down to pick up Ralph. Sitting in the bed of that truck with him, I didn’t care how many misses I had, or how sick I had felt.

“This is part of the process,” I explained to Ralph, telling him about the hunt. “You are going to be bad at everything until you do it enough, and that’s ok as long as you keep moving forward.”

At 18 months old, that didn’t sink in at all and he just poked the elk a few more times.